|

Notes from a short talk given as part of a panel discussion entitled ‘Designing the perfect photobook’

CG with Neil Pardington and Jonty Valentine, chaired by Libby Jeffries of Momento Pro at the inaugural Photobook NZ, Wellington, 2016.

photograph / Ann Shelton

As for the »perfect« book, I have no idea. I figure it’s entirely subjective. By that I mean every part must work. As a whole. All the parts. And be authentic to the tone and voice of the author and their idea. Nothing worse than mutton dressed as lamb.

I looked through our library at home, in search of »perfect« — mostly through Bruce’s extensive collection of photography books, in three-metre high shelves that the house is centred around — art, photography, design, typography, fiction, non-fiction — spilling out onto the floor, and into the studios ... and after looking at what I had pulled out, I found I’d gravitated towards books that mean something to me, whether personal, or just plain exciting. Or, that just feel really right.

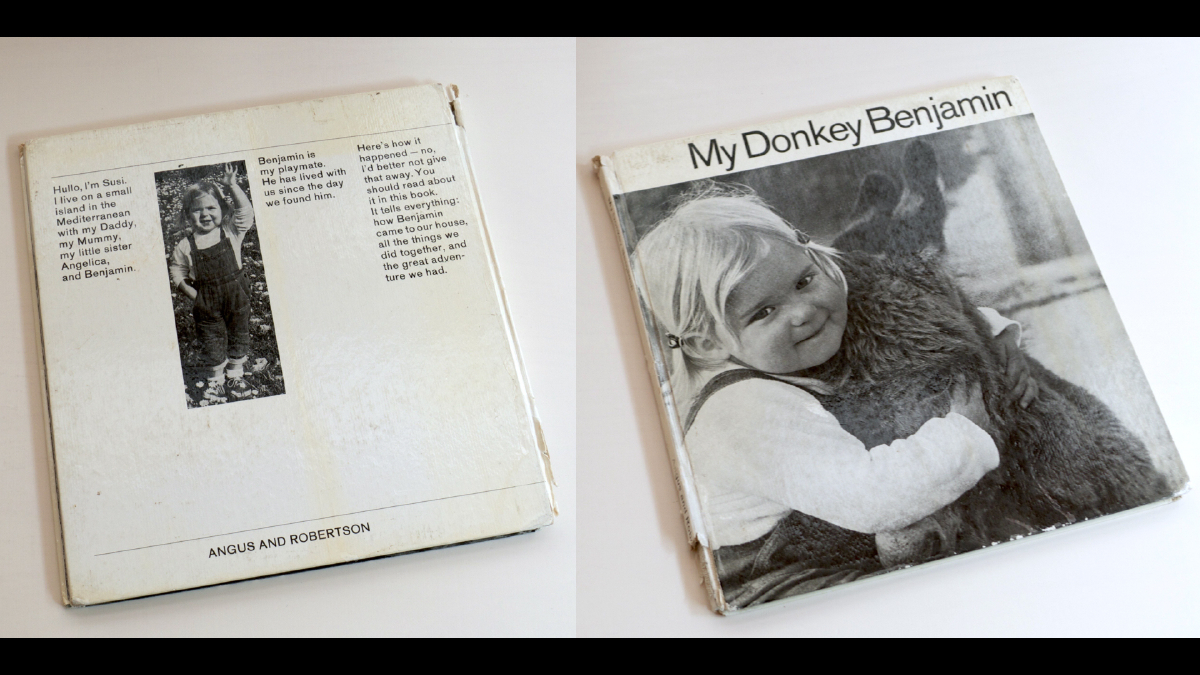

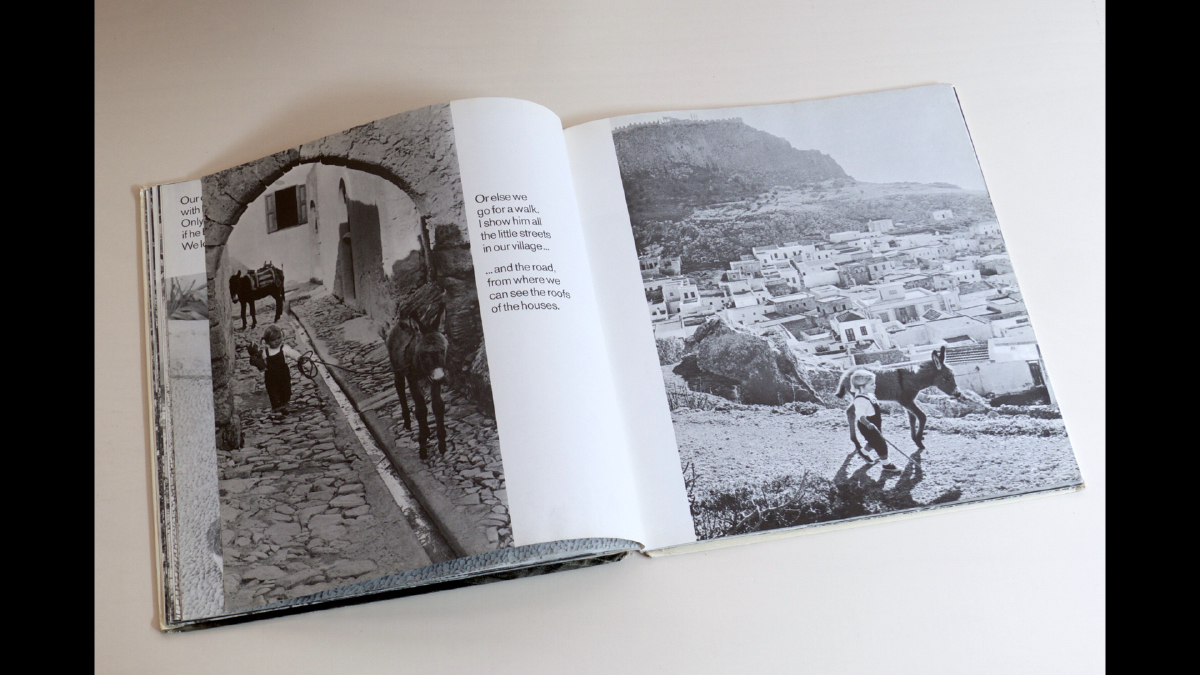

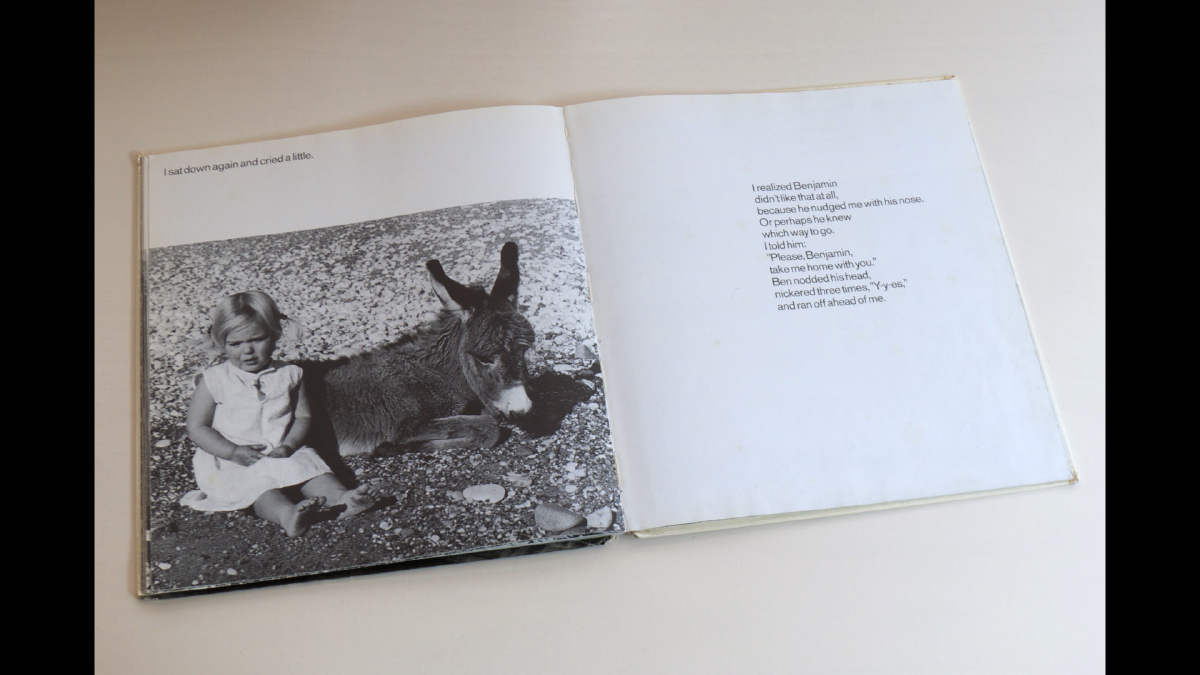

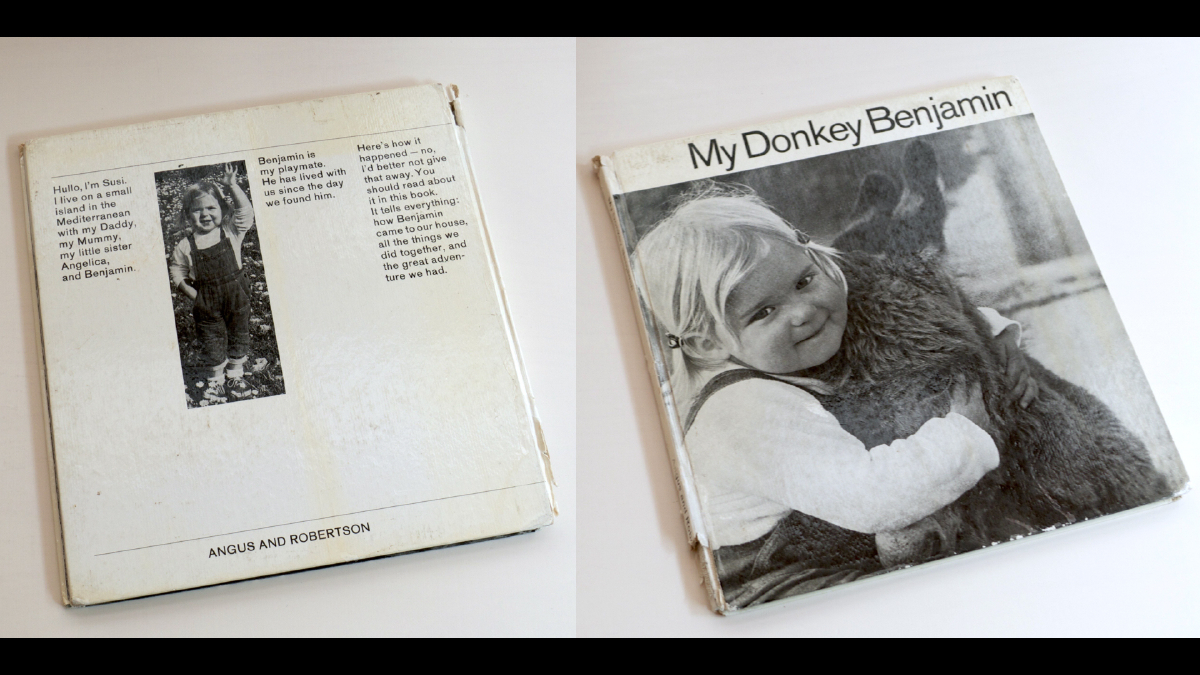

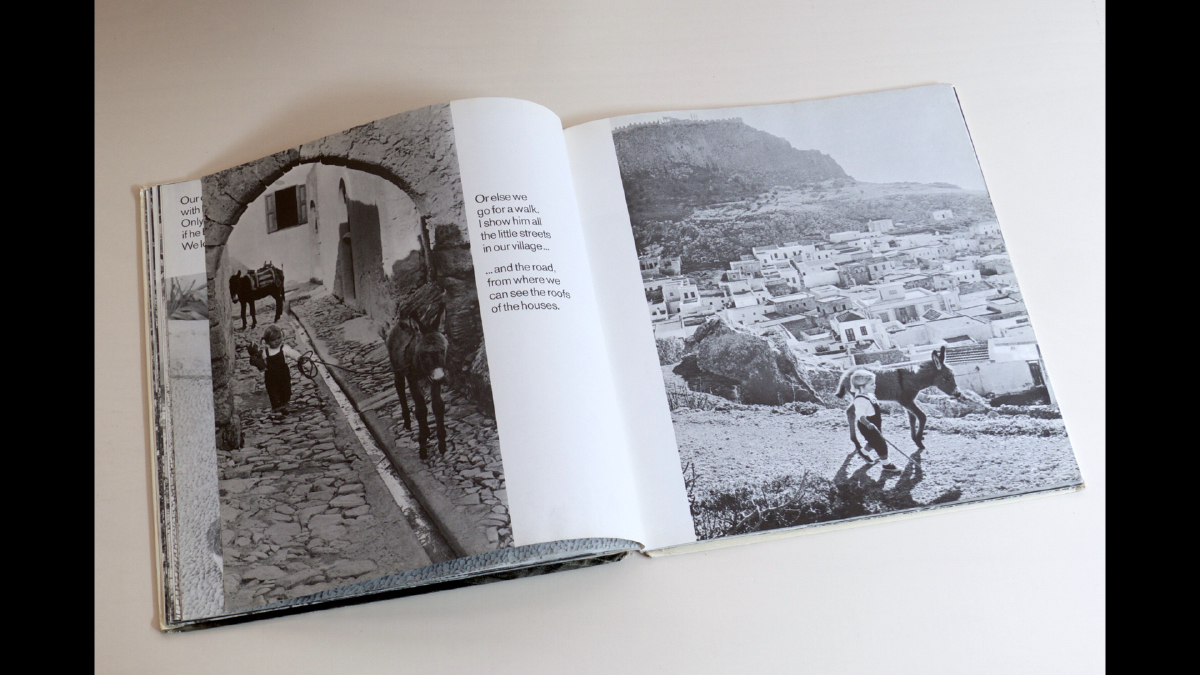

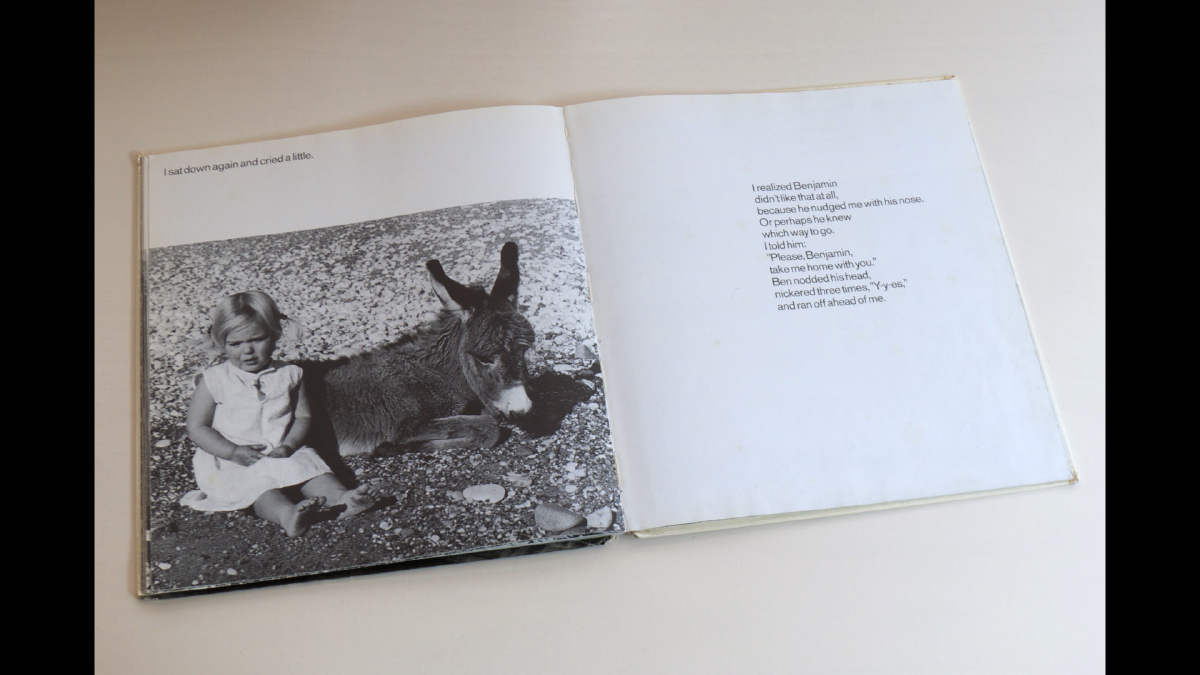

My Donkey Benjamin, 1969

One of several books, along with Grub the Bush Baby, Chi-Chi The Giant Panda, The Red Balloon, that I started out with, when I was small in the 60s.

I absolutely LOVED these books. You could say, they helped shape my sense of space, place, and journey. They were my Whakatane [small town Aotearoa New Zealand] window out, into other lives, other worlds.

Josef Sudek, 1956

Ever since I saw this book, I coveted the cover typography. Positive and negative spaces — typography meets architecture. Compositionally, only his name works — a serendipitous combination of letterform, as I discover later ... Inside, a classic volume, complete with silk ribbon, containing Sudek’s broad spectrum, atmospheric images, reproduced using photogravure.

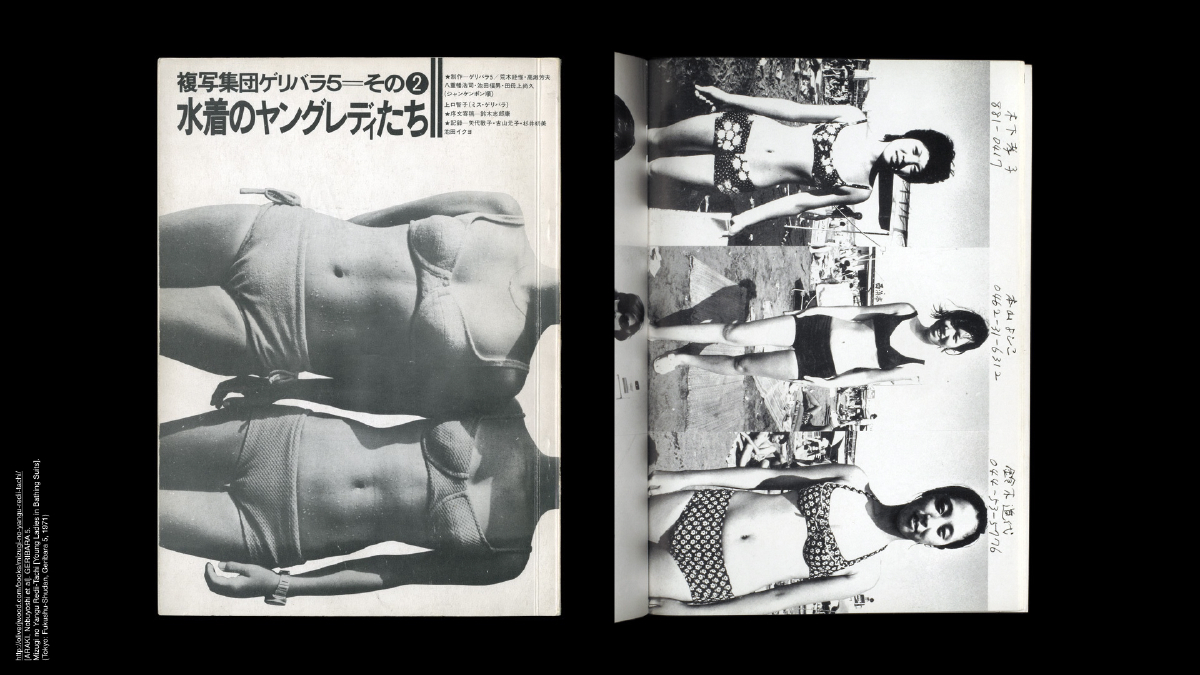

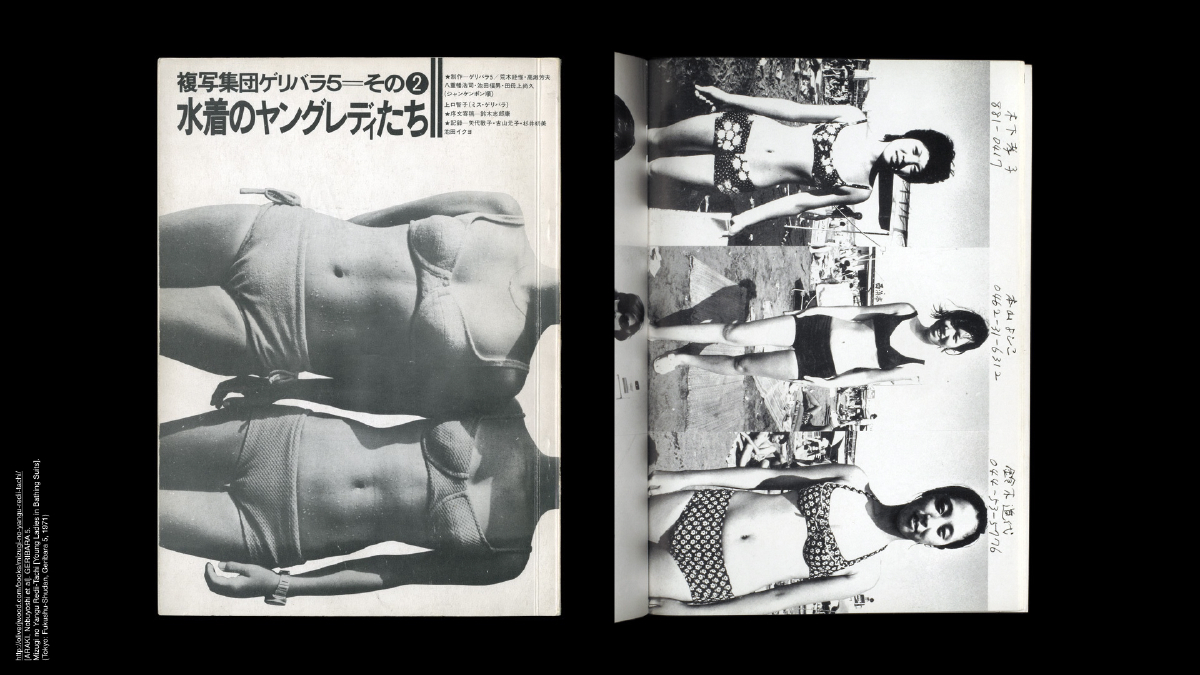

Young Ladies in Bathing Suits, 1971

Geribara 5—collective: ARAKI, Nobuyoshi, TAKASE, Yoshio, YAEHATA, Koji, TABOGAMI, Naohosia, IKEDA, Fukuo, KAMIGUCHI (Miss Geribara), Tomoko, GERIBARA 5

Conceptually this book is provocative. At first glance, the book could be read as somewhat benign, yet in the detail it is controversial: the trio of images per page is accompanied by each girl’s handwritten address and telephone number. According to Araki, around half are authentic ... but irrespective, the book is demanding of the viewer, and raises issues around privacy, and sexual harassment. The layout carries the content without diminishing or overstating: the back cover is a flip of the front, the landscape format images are set vertically, the book reads from right to left ... how the viewer chooses to read — whether crossways or upright, the emphasis and focus shifts.

Telex Iran, 1984 / 1997

Gilles Peress

It was Bruce who introduced me, in the 1990s, to the work and books of French photographer Gilles Peress, and this extraordinary book — a book of its time — and to this day. A large-format book, including an essay, the photographs were made during a five week period from Dec 1979 to Jan 1980 in the days of telex (messages sent via telephone and printed by a teletypewriter) ... back and forth from to the staff at the Magnum office in Paris (including Natasha Chassagne, who Bruce first met in 1985), the messages are printed as if captions to the photographs. Designed by Gilles Peress + Claude Nori, this is a big bold collaboration driven by the photographer, where content is king.

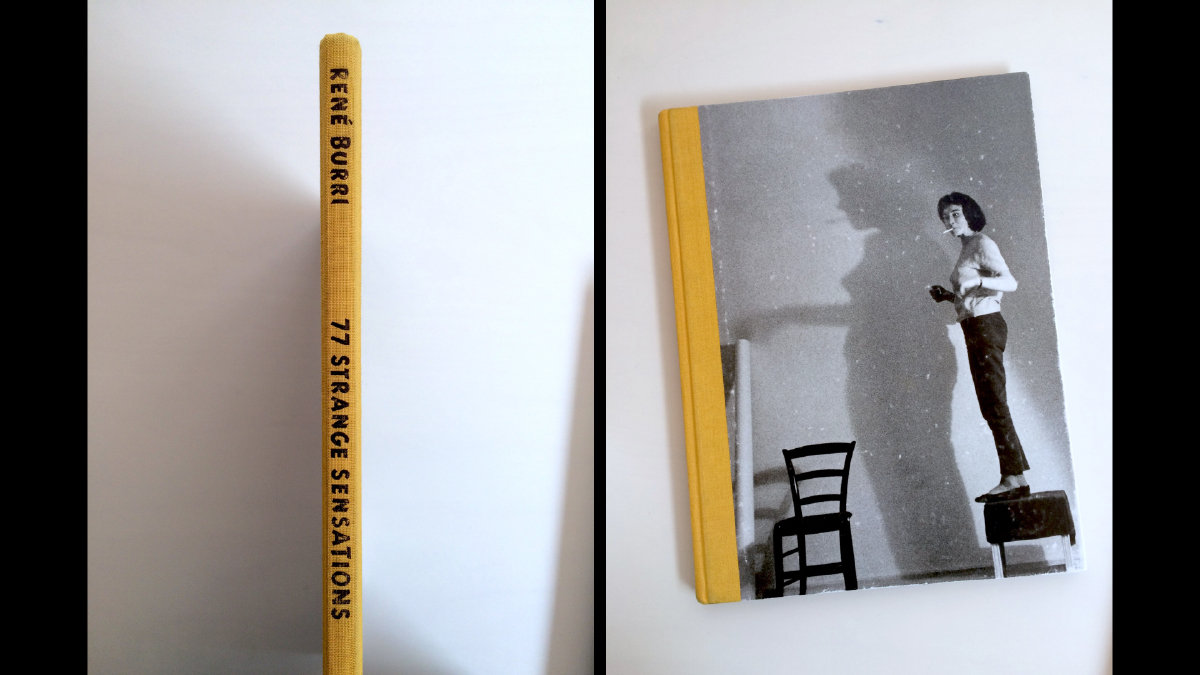

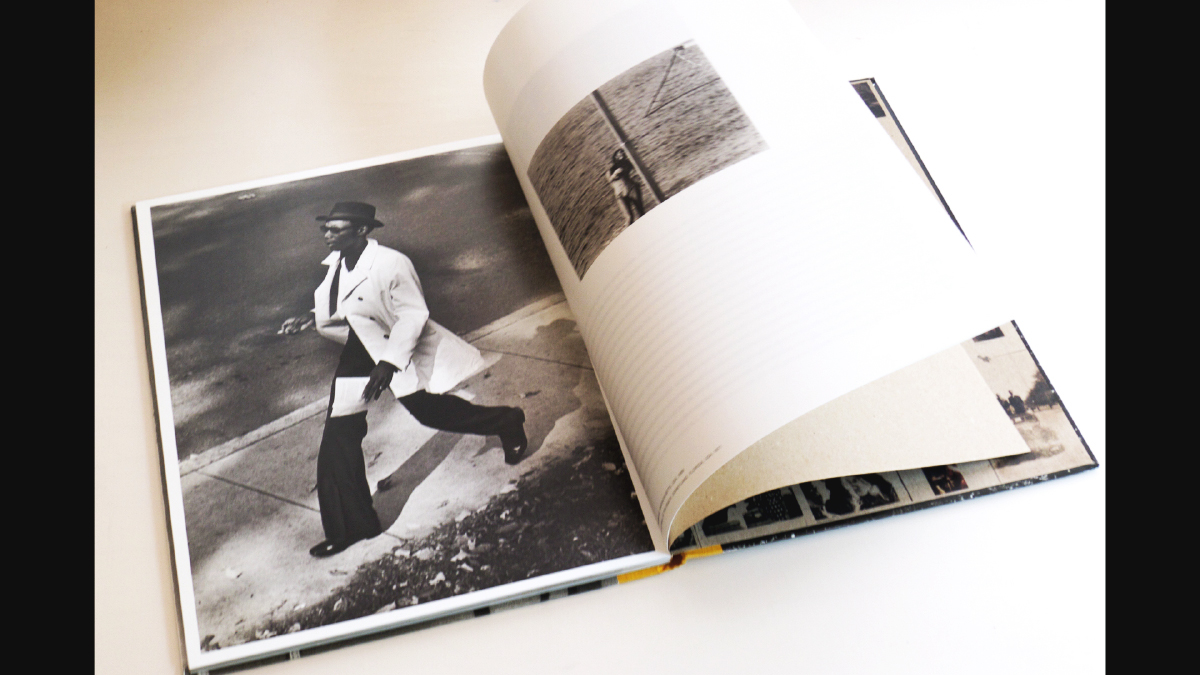

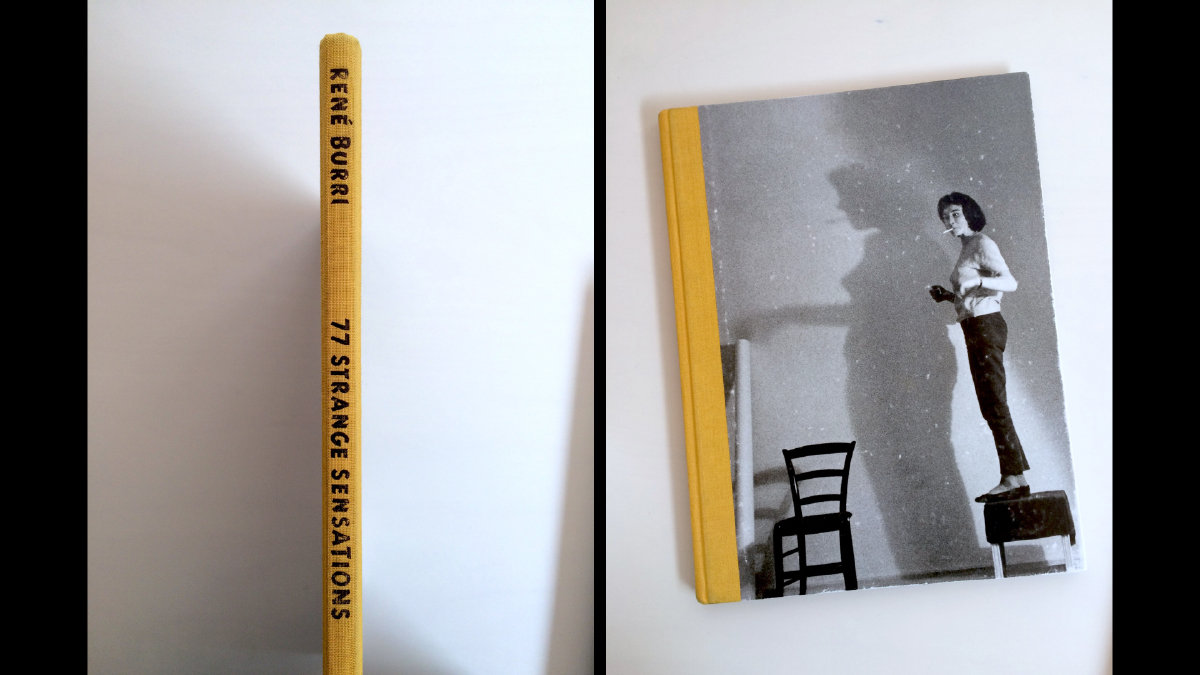

77 Strange Sensations, 1998

René Burri

I found this book in Basel, Switzerland, at the start of a journey to follow in the footsteps of Rebecca West (but that’s a story for another time), where I was visiting influential teacher, graphic designer and typographer, Wolfgang Weingart and his wife Kate Wolff. While staying with them, I witnessed Weingart constructing, what I would say is the closest to »perfect« in graphic design terms, his book — the tiny maquette sat on the dinner table: My Way to Typography. Meanwhile, Bruce was in Kosovo just after NATO had gone in — we’d been apart for weeks already, and when I saw 77 Strange Sensations, it stood out.

Inscribed on the title page — I am reminded — this book was filled with connections, leading us towards each other. In that respect, alone, I regard this as a wholly successful book! But what I love, is the feel, the atmosphere. The whole sensation.

In the colophon it notes: “Conceived, designed, produced, marketed and out on the runaway by Dino Simonett”! There are three books in the series, each one whacko and wonderful ... and years later in Paris, René Burri told us over lunch at his place as he busily inscribed the other two books with watercolour paints, as he was wont to do ... that he never liked the books!

Yet, all of the parts, the random nature of the sequence, the insertion of a story, the un-precious typography, the tone and feel of the paper, the dimensions — the book is alive!

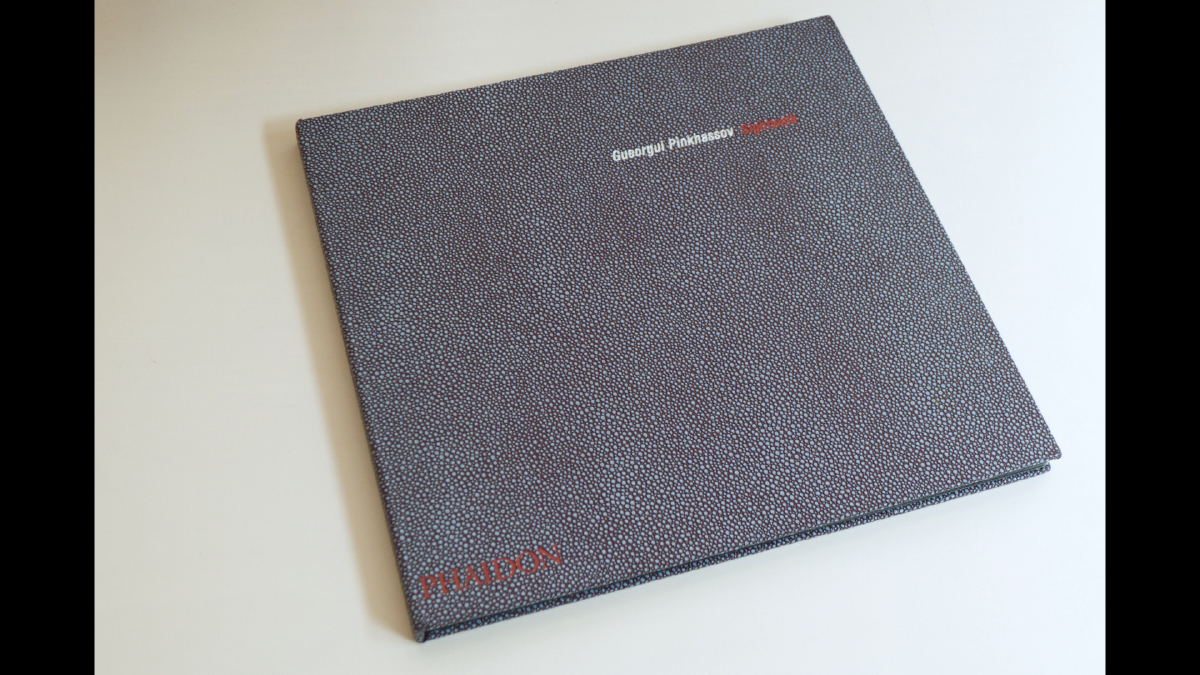

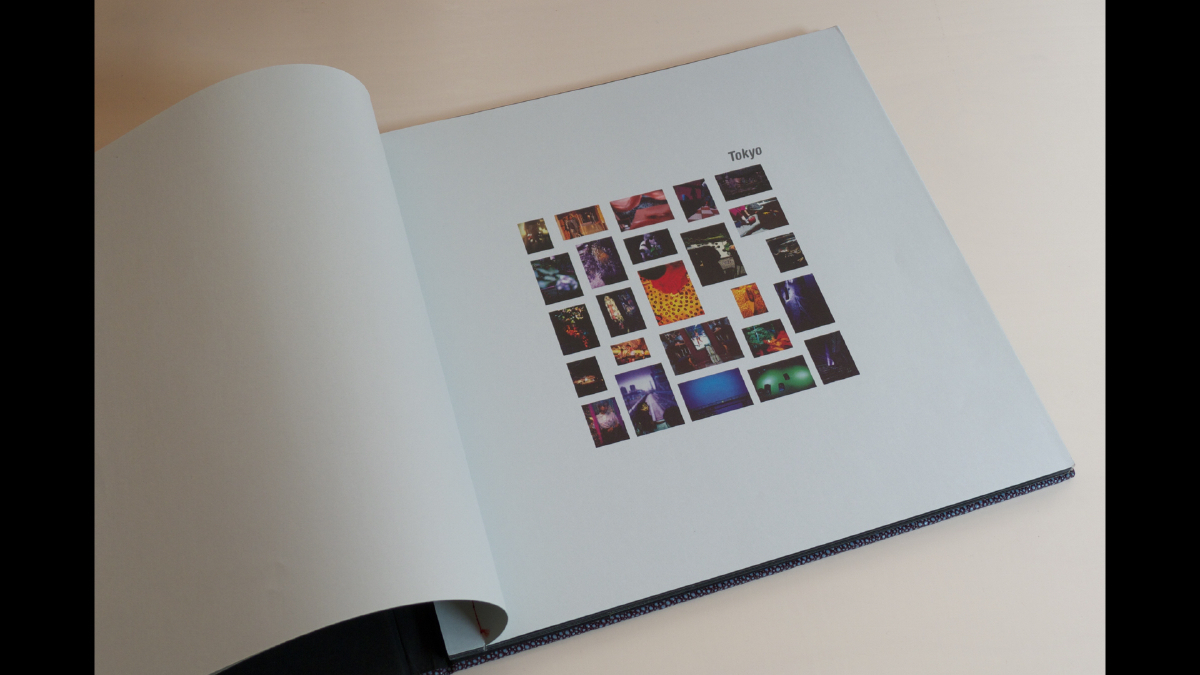

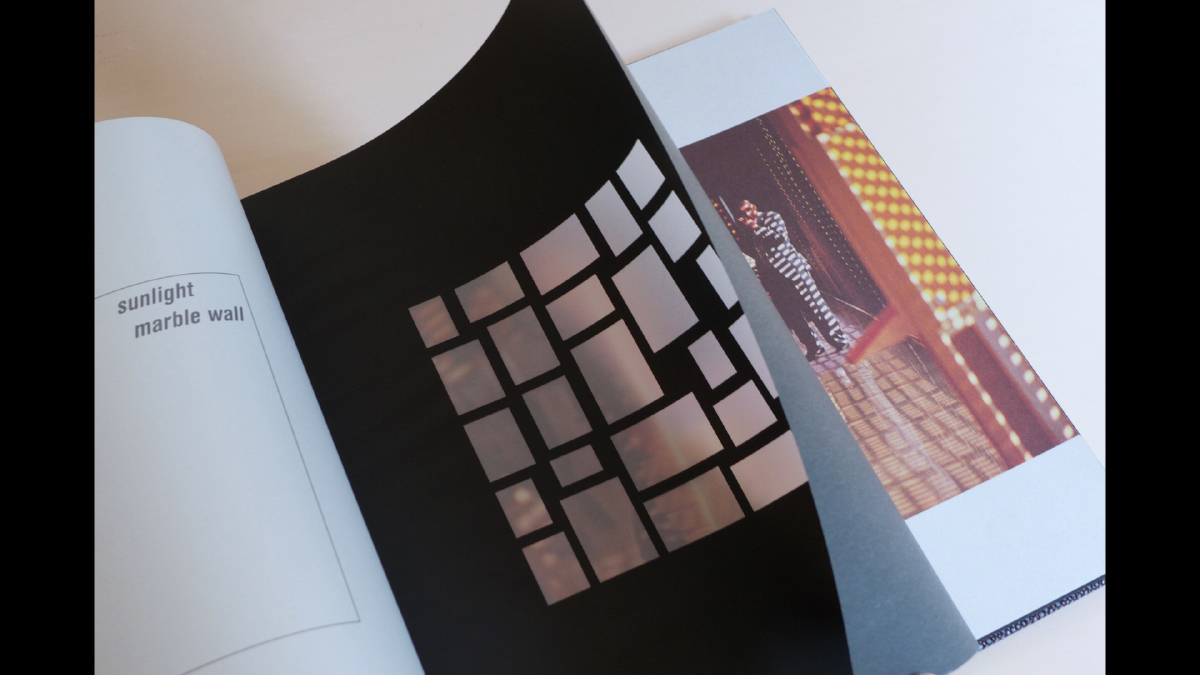

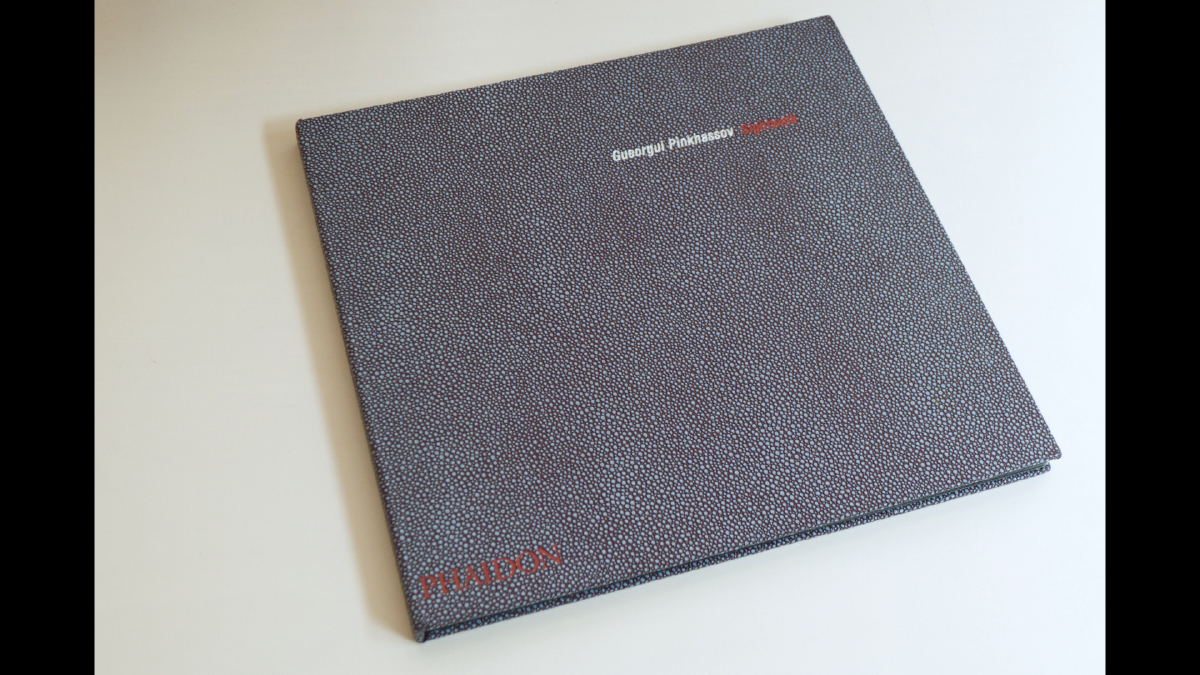

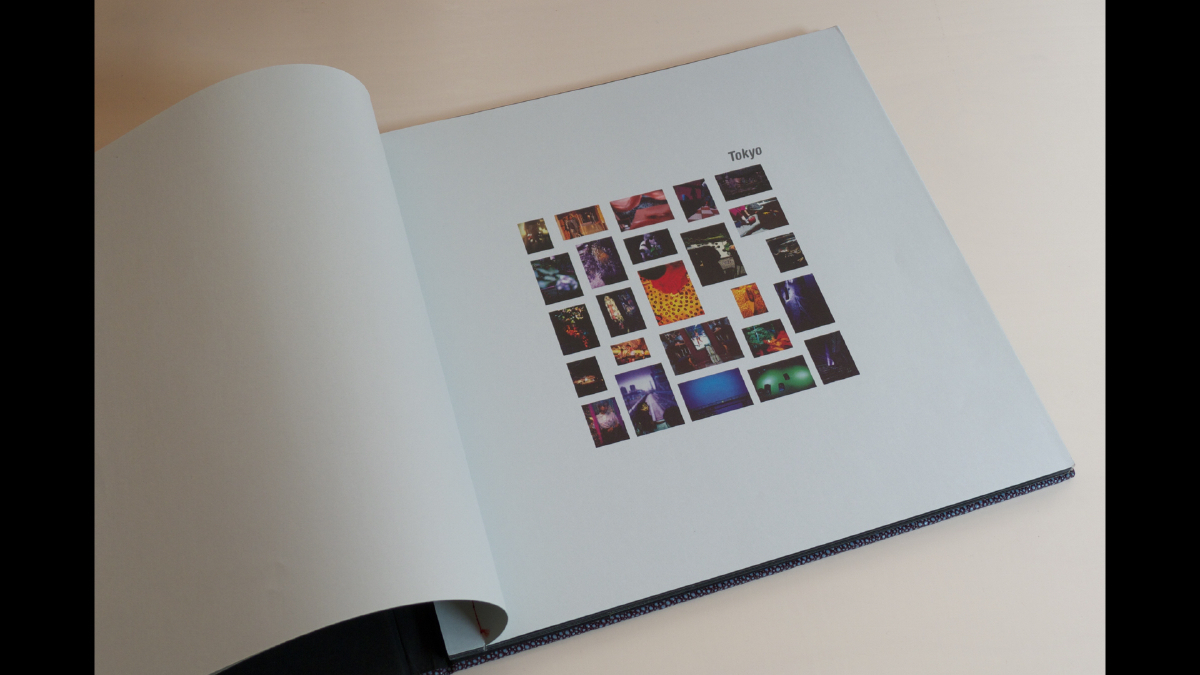

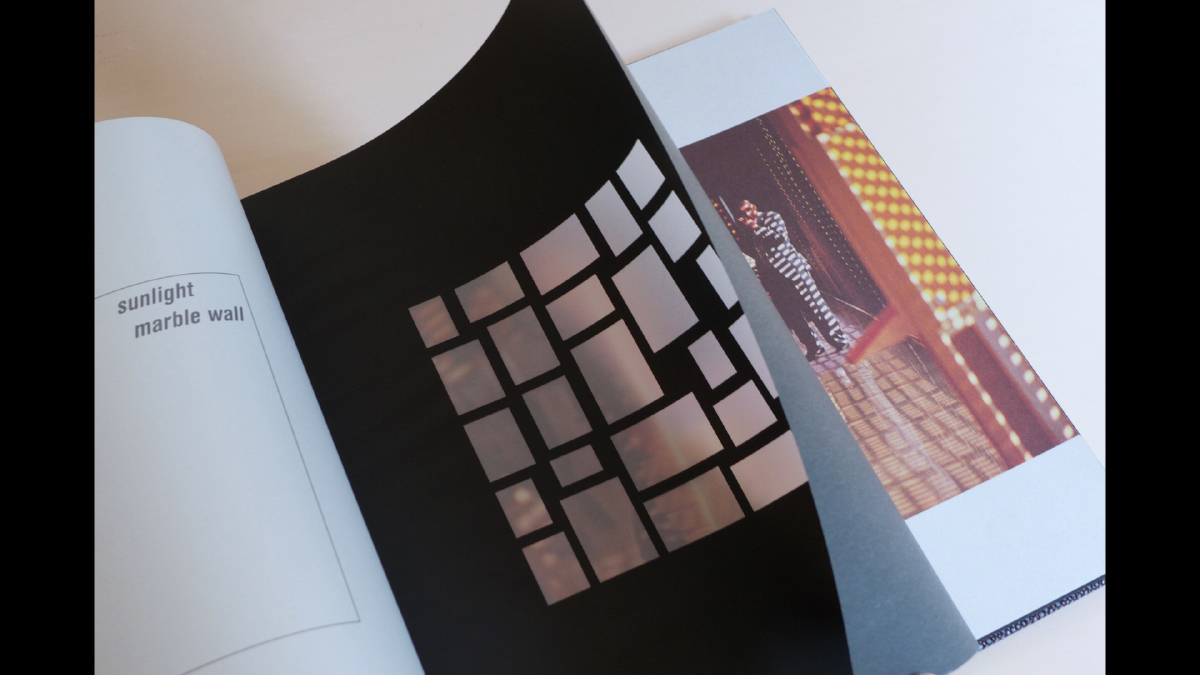

Sightwalk

Georgiou Pinkhassov

To be truthful, I probably love the photographs, the eyes, of Pinkhassov more than the design of this book — square format rarely works comfortably as a book form (not that I am looking for comfort!), but in this case, and in My Donkey Benjamin, it succeeds.

There’s a kind of lavishness, that borders on frivolous and a concept that could be literal, but the designer at Phaidon just got away with it. The materiality of the book is strong — French folds, translucent sheets, stab stitching, textured cover — but the images stay strongest.

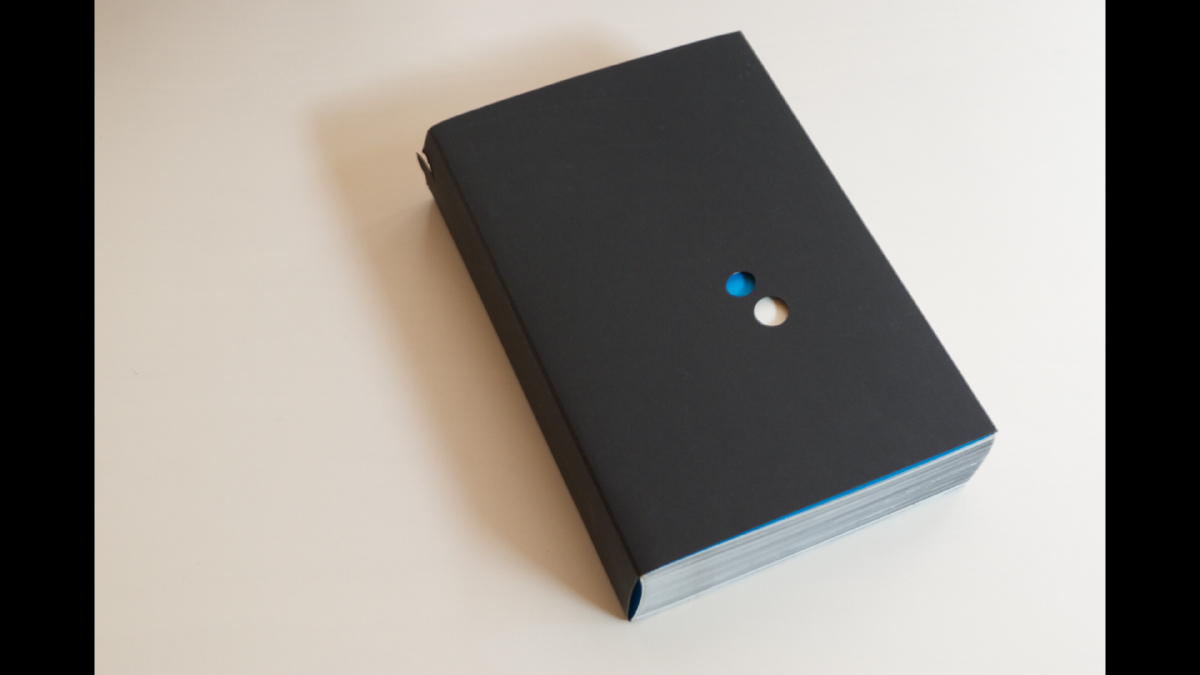

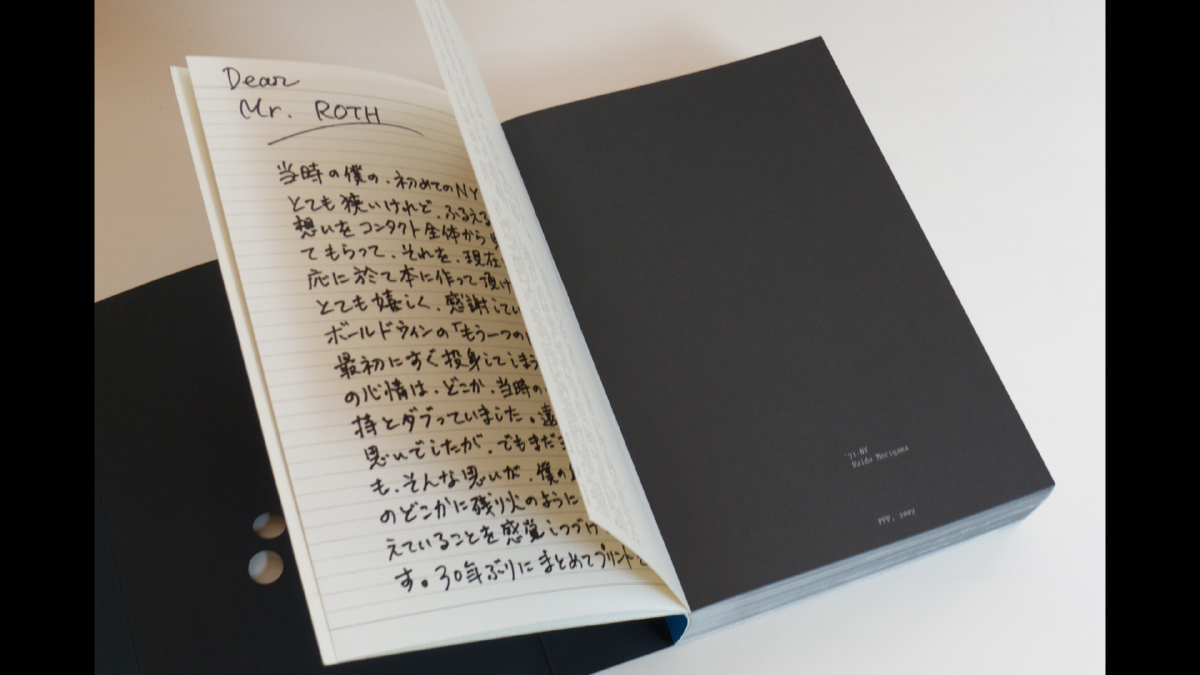

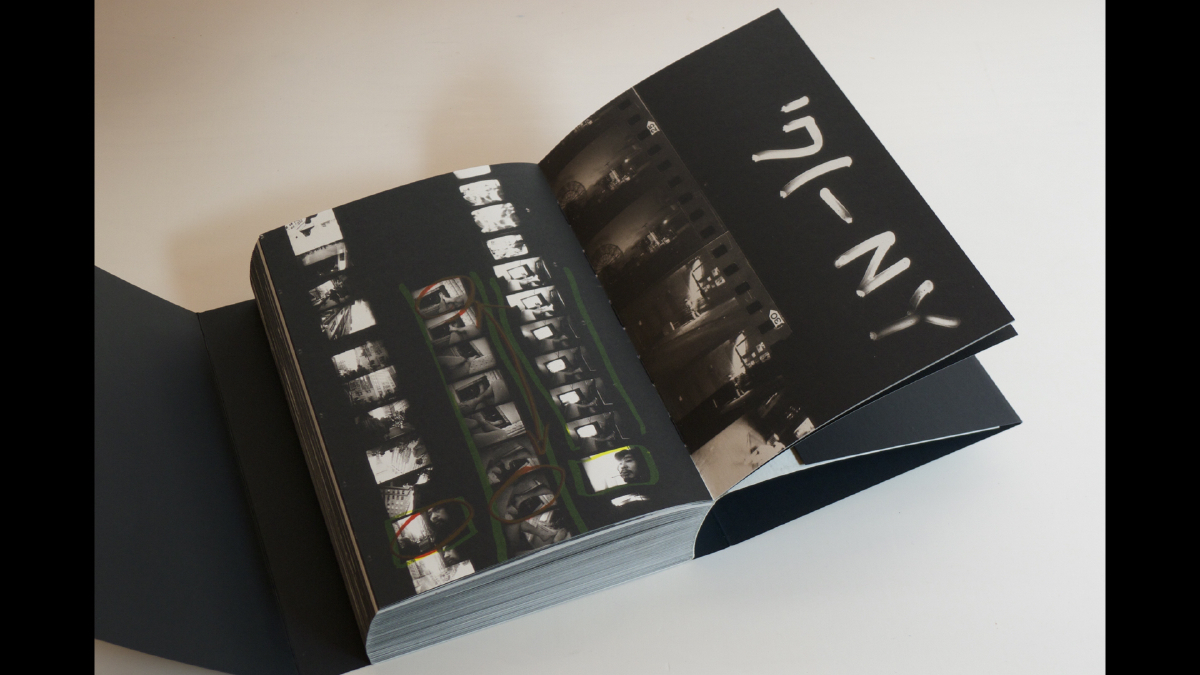

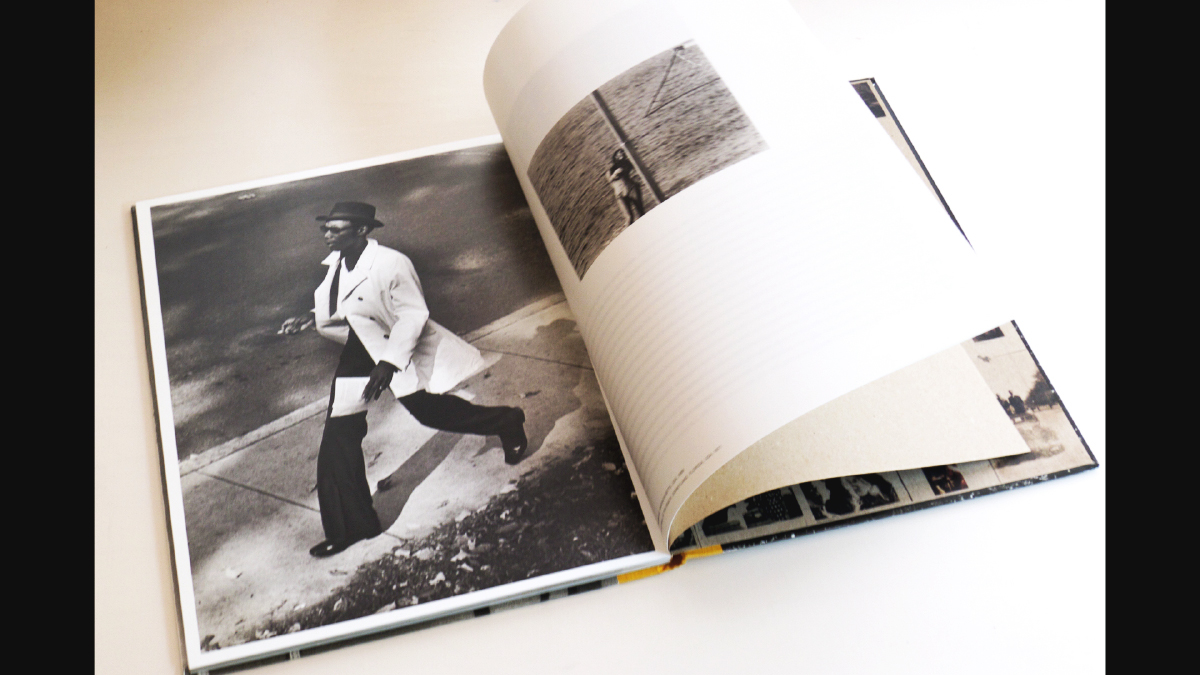

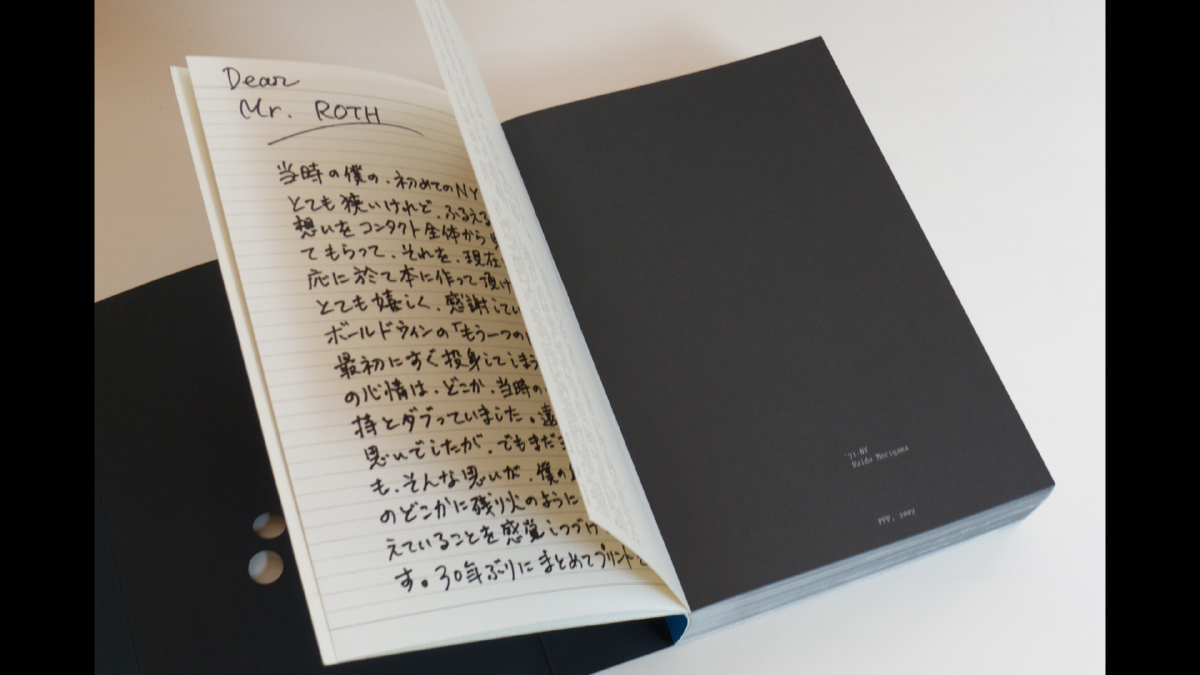

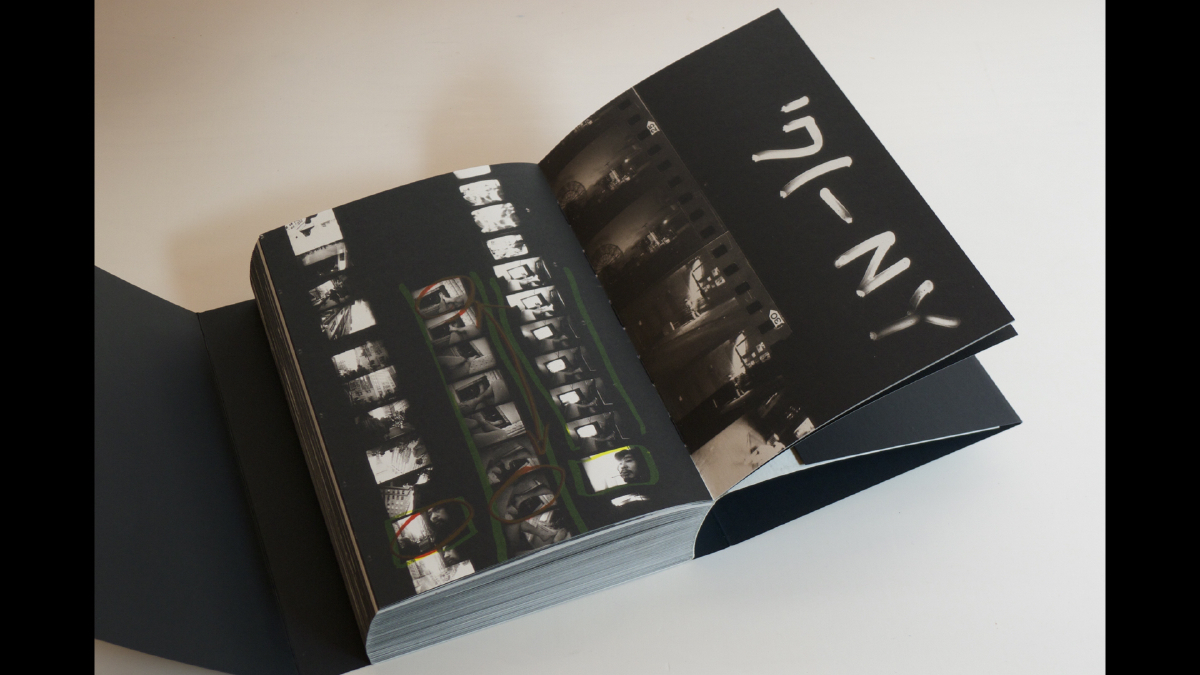

’71—NY

Daido Moriyama

Admiration of Moriyama aside — the concept — revisiting contact sheets 30 years on, from a body of work made back in 1971 is a challenging one to do justice. Back then Moriyama spent a month staying in The Chelsea Hotel with a friend and graphic artist, Tadanori Yokoo, looking at Weegee — and making his own pictures which became the photocopy book Another Country.

’71 — NY is a stunning filmic sequence of full bleed images in another city, wrapped in the weight and smell of ink on paper, accompanied by an excerpt ... from James Baldwin’s Another Country (1963), an interview with Moriyama by Andrew Roth (2001), and an original 2,500 word essay by Neville Wakefield.

The edition is a collaborative work designed by gallerist and bookseller Andrew Roth, with Alexander Gelman’s Design Machine. It feels good. The up front nature of it, full bleed images, the ease of binding, nothing sticks or is awkward, and if the loose jacket falls, you can catch it with two fingers through the holes!

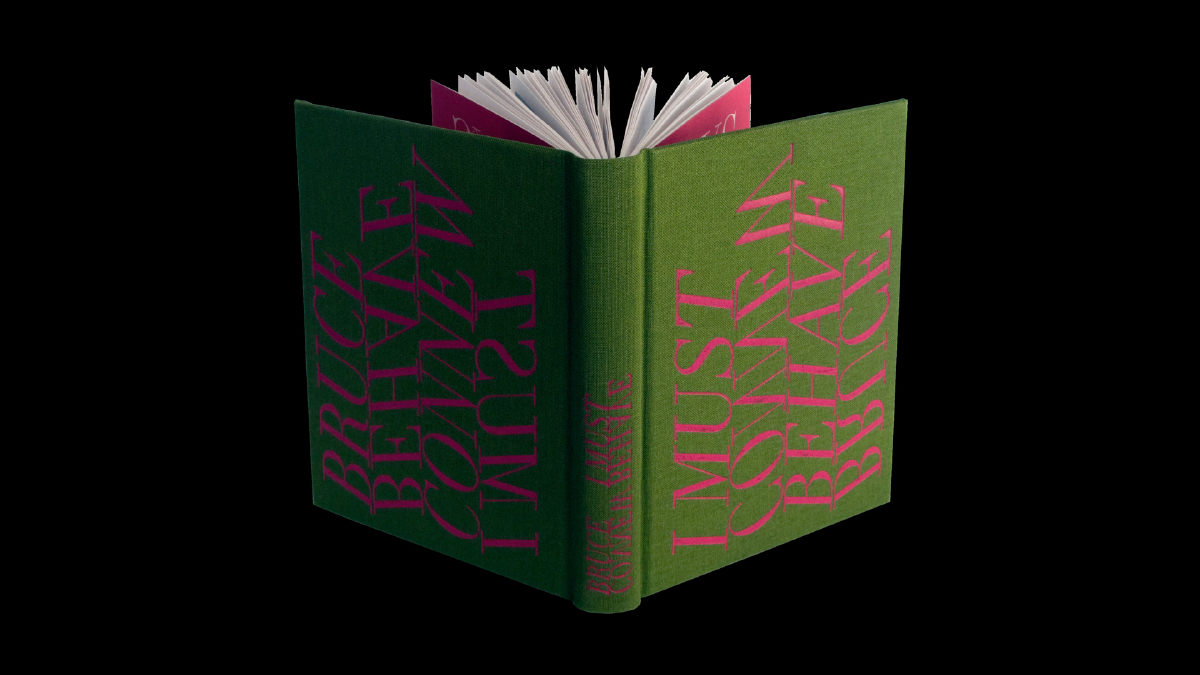

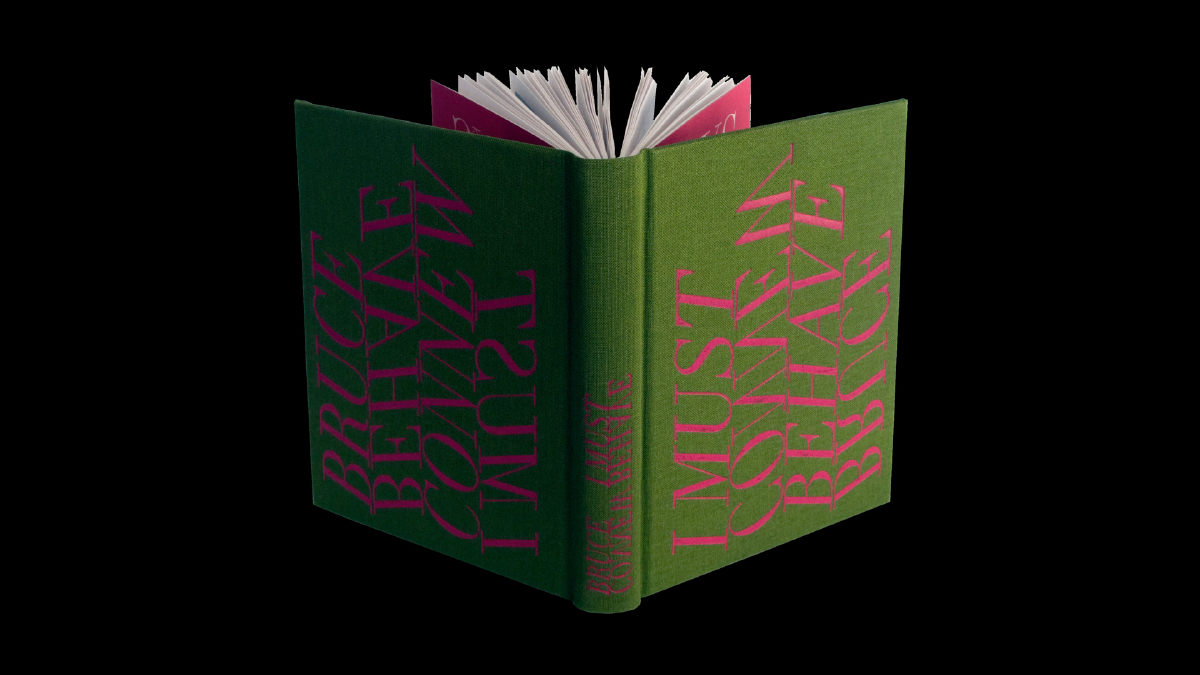

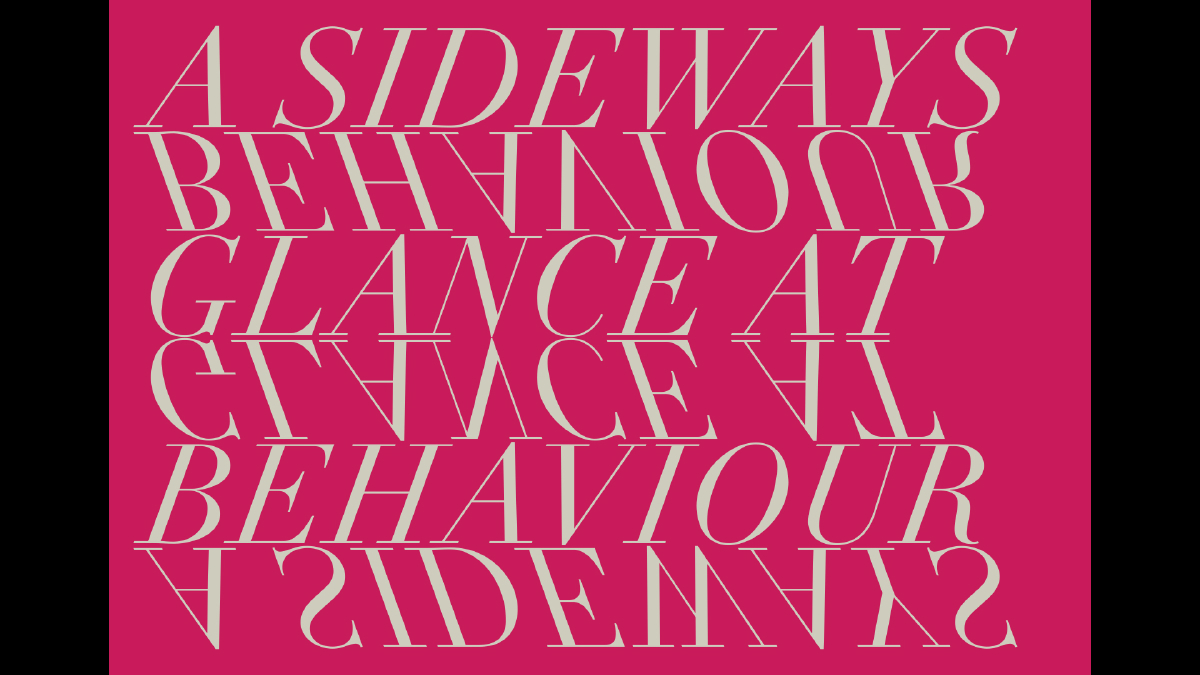

I Must Behave, 2009

Bruce Connew

The second in the ‘I’ trilogy of artist books which explore themes of behaviour and control. In the first, I Saw You, we are voyeurs on private moments in public spaces. In I Must Behave, the typography is a response to the over-arching idea of control, and how it modifies behavior. The third, I Drive You Crazy to the Moon, awaits patiently, unpublished.

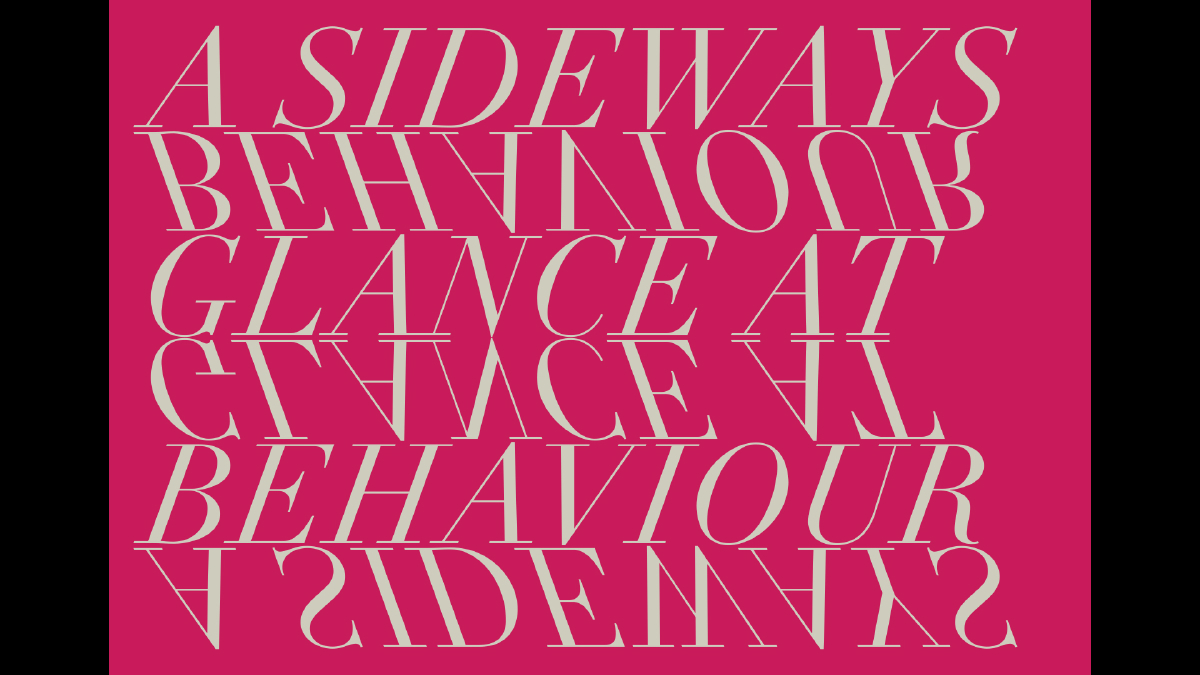

The ambiguities, the tricks played out in the images in I Must Behave — the pairings, the layers of meaning — are conveyed in the typographic titling. Throwing the title up on its side causes a behavioural response, not dissimilar to Young Ladies ... (I now make the connection!) — I watch a reader take the book, they turn it sideways, instead of shifting their gaze or moving their head, as they might with a work out of reach. Inside, the reader is given more of a clue, with the words “A sideways glance at behaviour” where the mirrored text plays again ... Not wanting to force italicise the letters, I flipped each word, and discovered how neatly this conveyed the content — and intention of the artist.

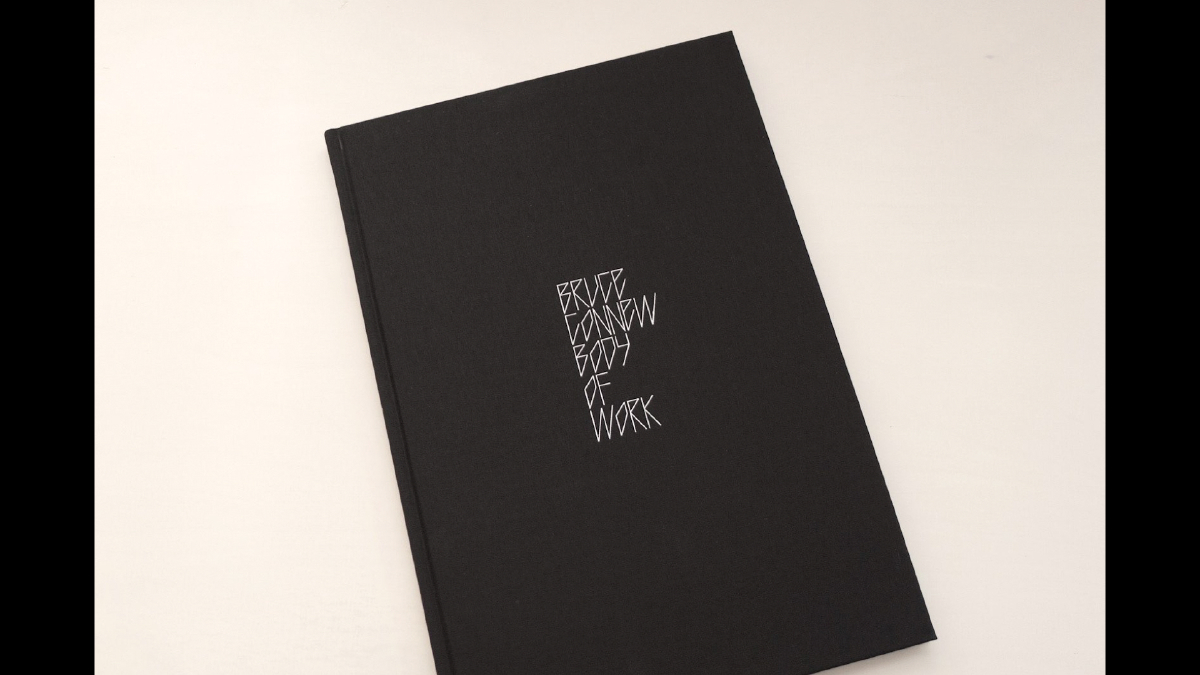

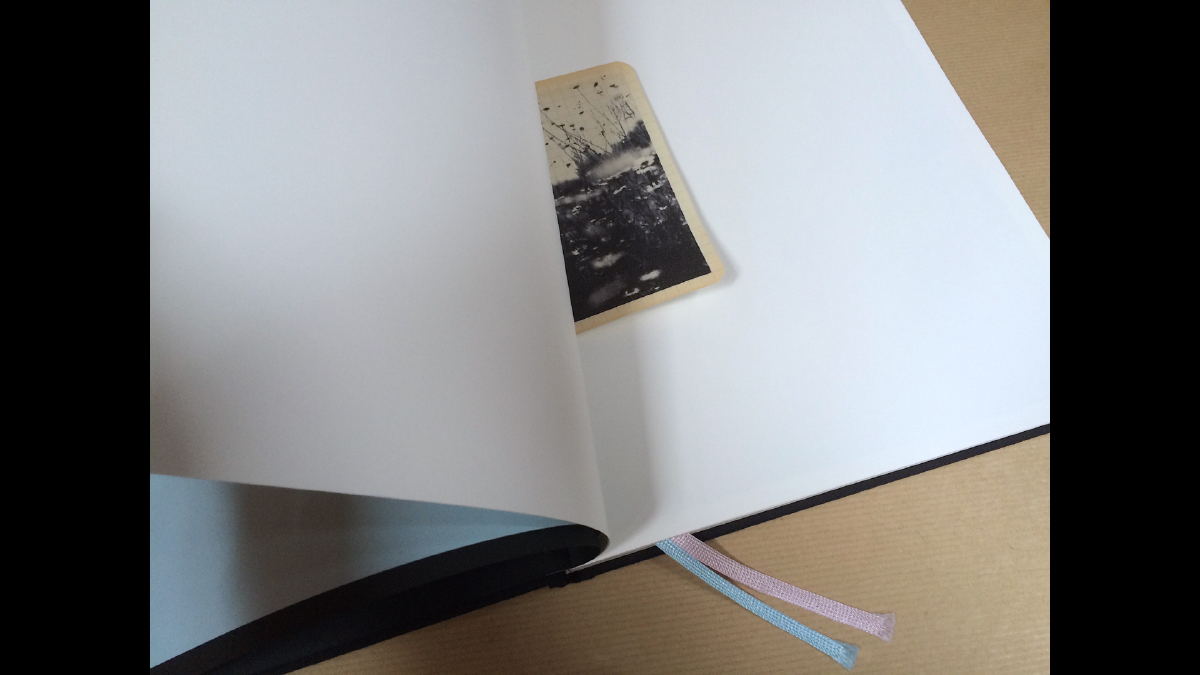

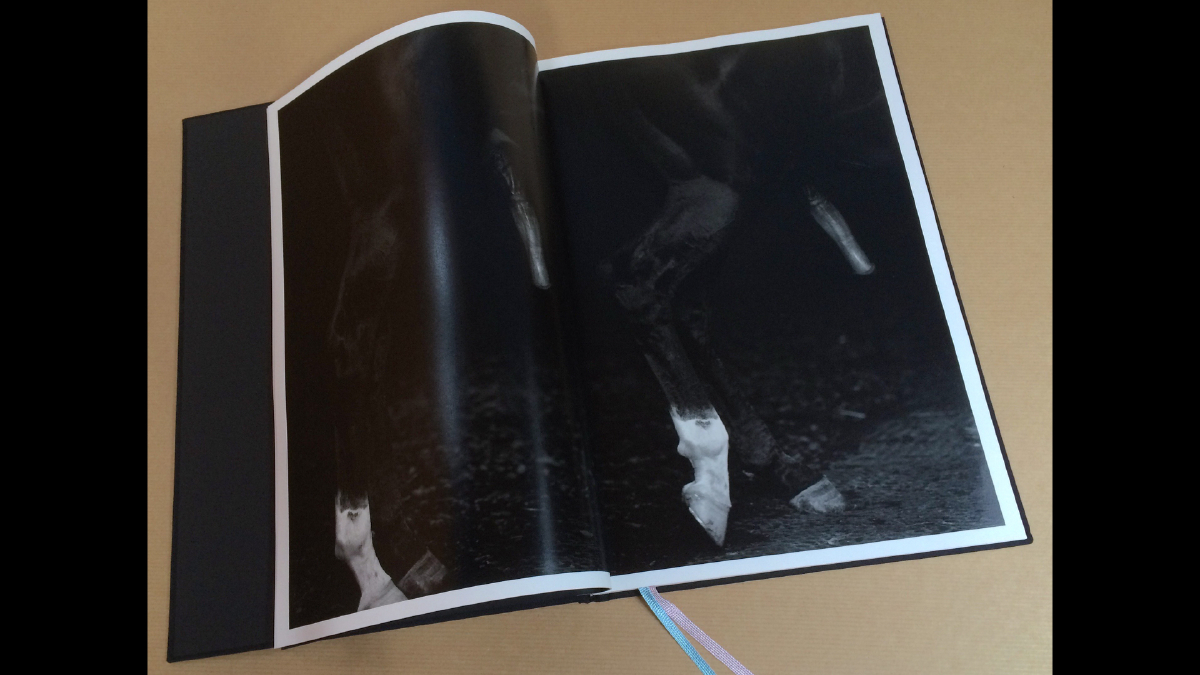

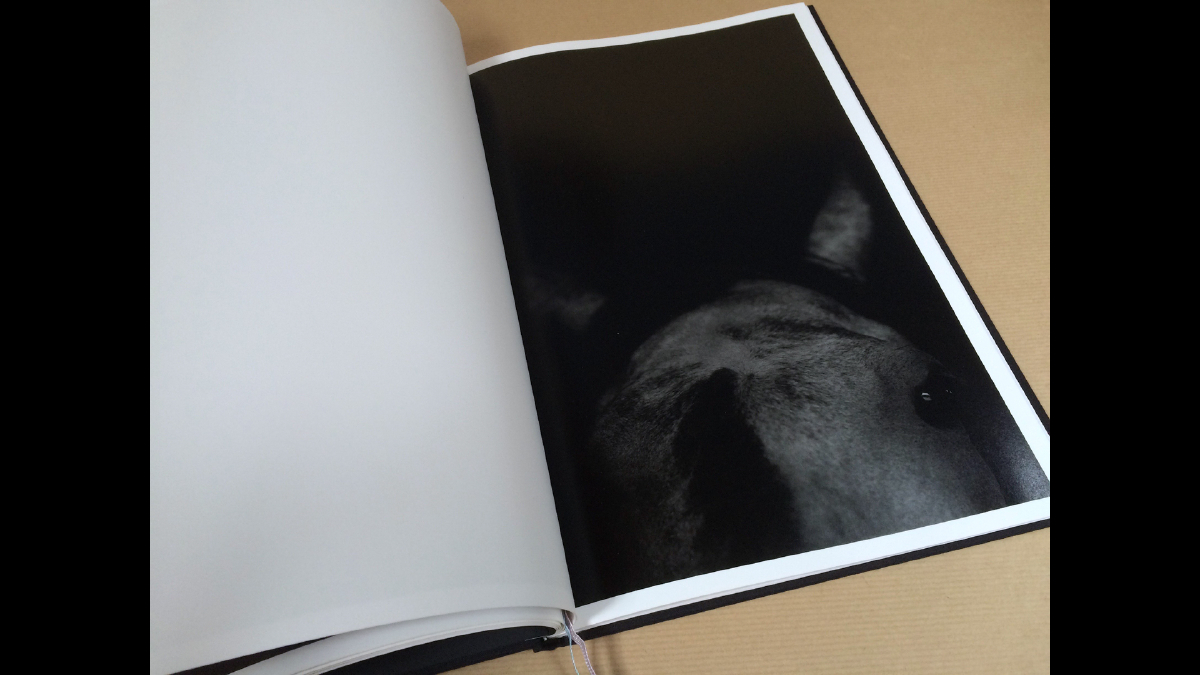

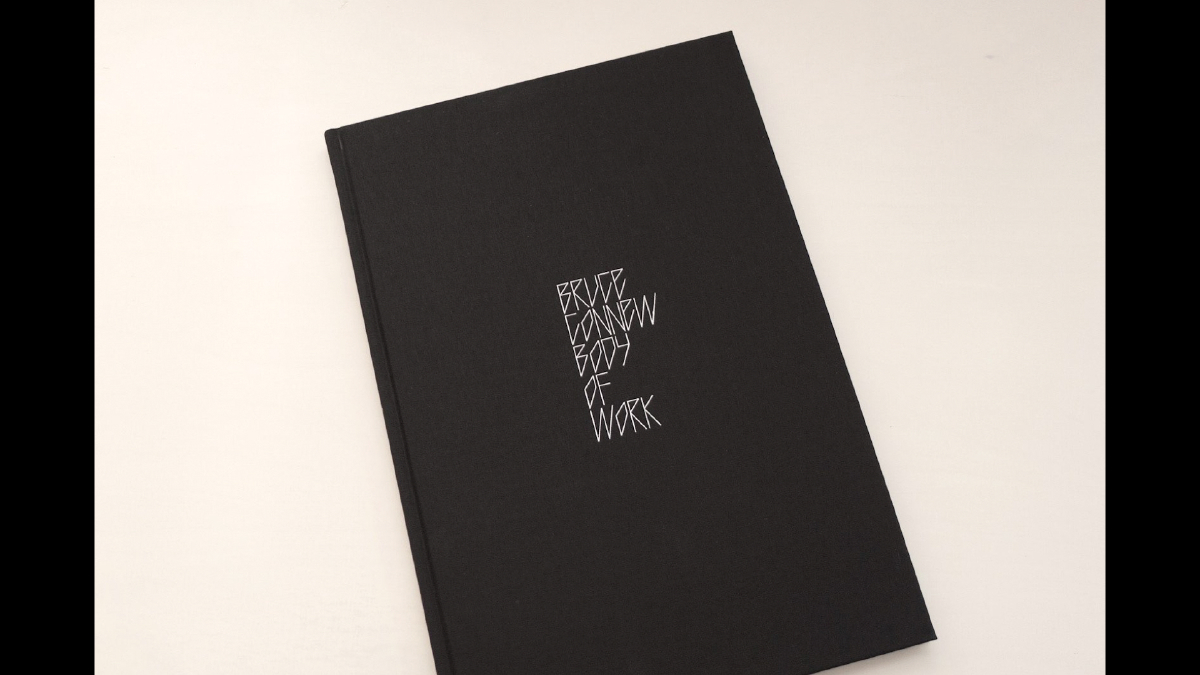

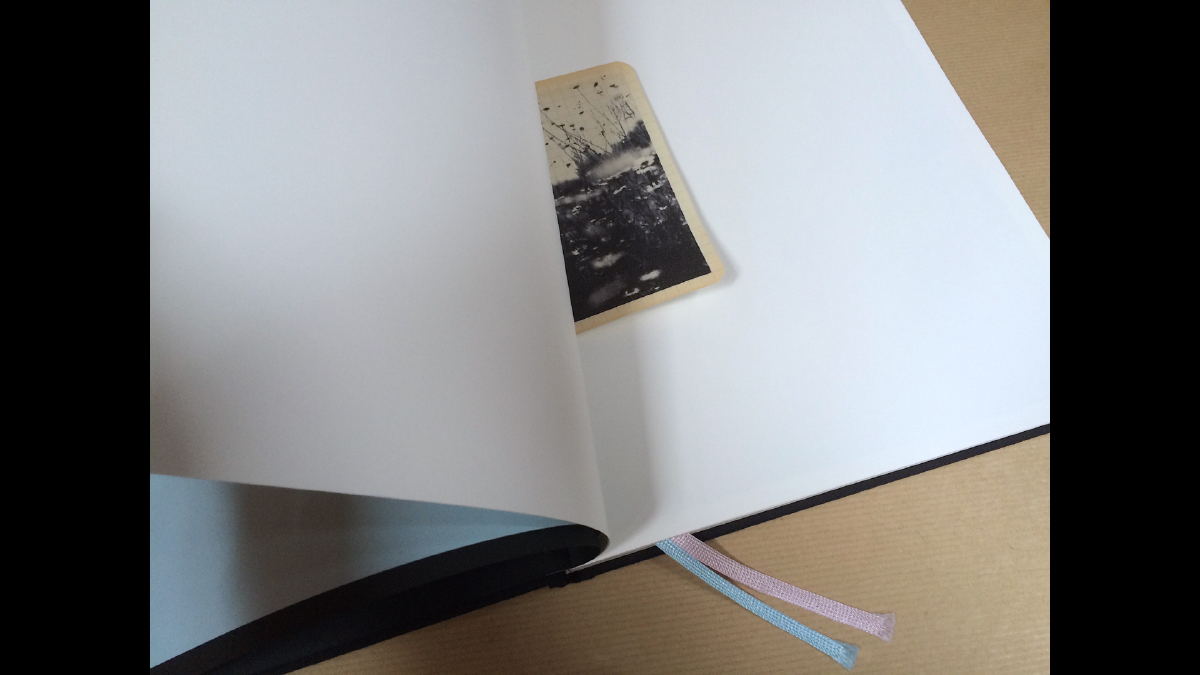

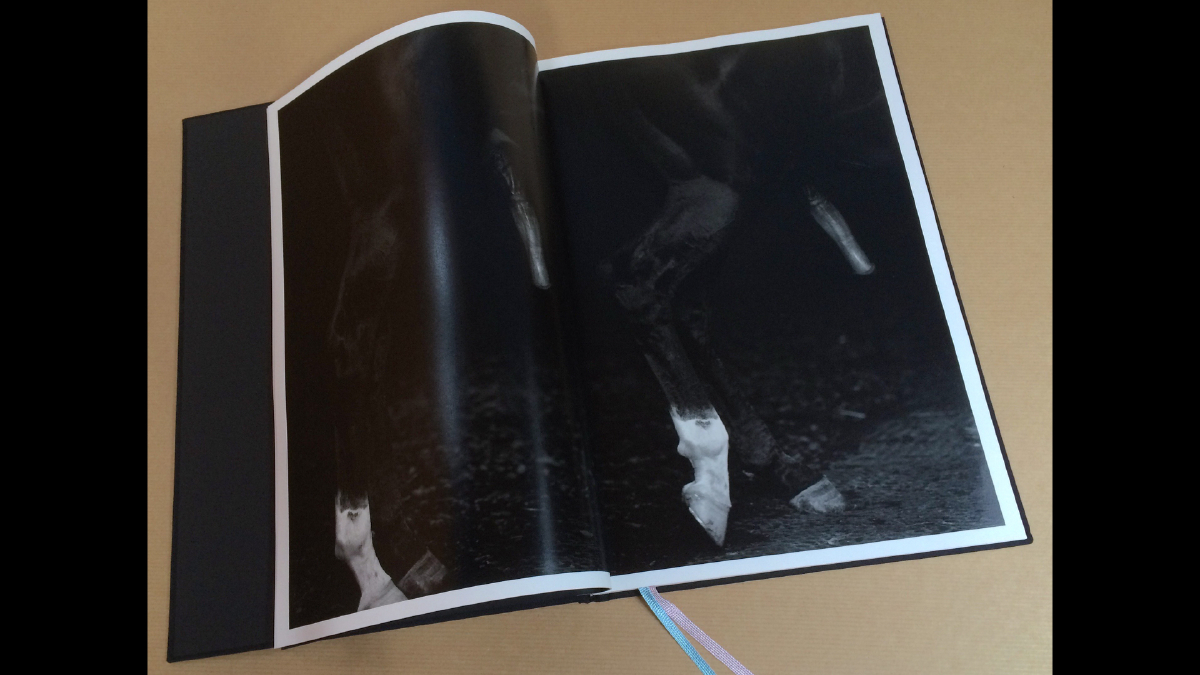

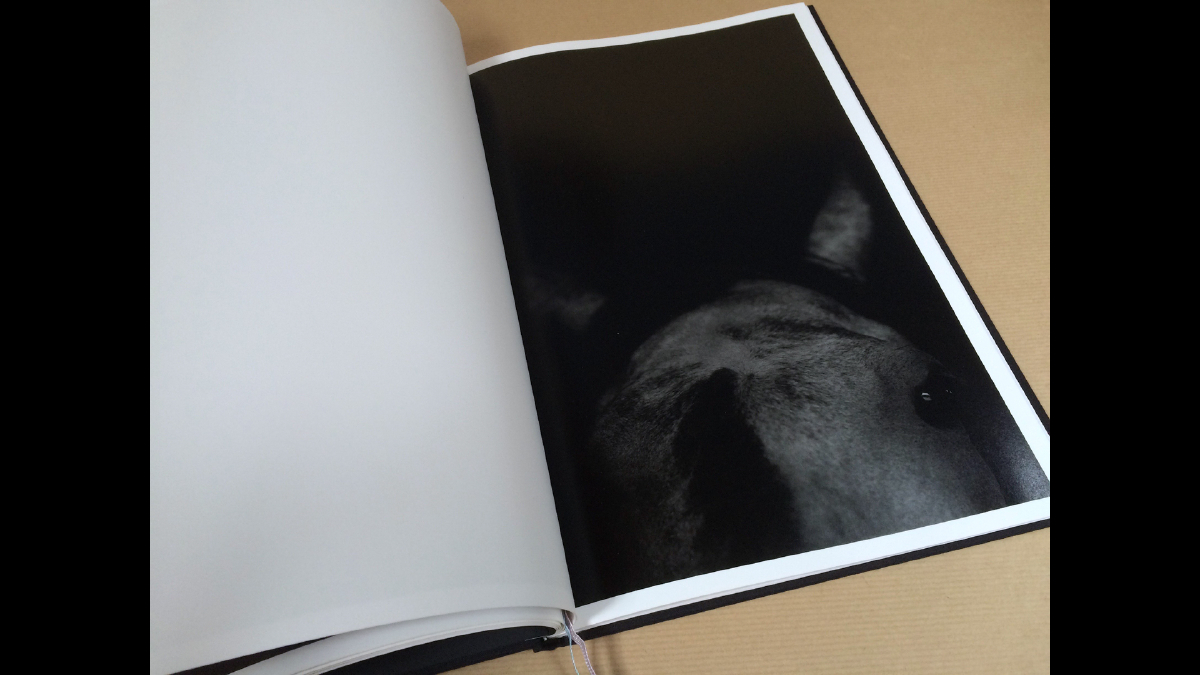

Body of Work, 2015

Bruce Connew

Our latest collaboration on book design, I finish with Bruce’s Body of Work, launched yesterday here in Wellington. Again, as typographer and designer, my response is to the content, the photographs and the concept in concert with Bruce ... minimal intervention ... typography, composition, materiality ...

Through the images I see isolated bright white flashes, markings on the forehead or the hoof, the splatter of wet, glistening in the deep black tones. By constructing letterforms out of thin lines, I found a rhythm and rigour that felt really right, not only for the nature of the work, but also for the particular combination of letterforms, words and overall shape.

As friend and type designer Kris Sowersby commented when I showed the title — “Real punk, has good attitude. But it won’t work as a typeface!” And I think maybe, he is right. My intention was not to make a typeface, but rather to find a way to articulate in an authentic manner the intention of Bruce, and his concept as the photographer, the artist.

notes and slides / Catherine Griffiths © 2016

|

|

04 writing & critique

Walk With Me

by Stephen Cleland

curatorial essay, »Catherine Griffiths: Walk With Me«, Te Wai Ngutu Kākā Gallery, Aotearoa NZ, July 2025

Blood lines

by John Warwicker

exhibition review, »Catherine Griffiths: Out of Line«, Eye Blog, UK, June 2025

On the Expanded

by Megan Patty

curatorial essay, »Catherine Griffiths: Out of Line«, The Design Gallery, University of Melbourne, Australia, May 2025

The Shapes of Sound

by Ela Egidy

curatorial essay, »Catherine Griffiths: Out of Line«, The Design Gallery, University of Melbourne, Australia, May 2025

Read this space

by John L. Walters

book review, »catherine griffiths : SOLO IN [ ] SPACE«, Eye, UK, Spring 2023

Notes from a short talk at Photobook NZ, 2016

by Catherine Griffiths

‘Designing the perfect photobook’ 12.15 – 1.15pm

How do designers and photographers work together to make strong photobooks? Three of New Zealand’s leading photobook designers (with enough awards between them to sink a flotilla) discuss the language of the photobook, materiality and the emergent e-book.

Catherine Griffiths – Independent designer and typographer

Neil Pardington – Photographer and Base Two creative director

Jonty Valentine – Graphic designer and co-producer of The National Grid

Chair – Libby Jeffery, Marketing Manager, Momento Pro

related links

PhotoForum Photobook NZ

Making Noise

by Catherine Griffiths

contribution, Alphabettes Soup: 2015–2025, Bikini Books, Portugal, March 2026

Walk With: A Survey Exhibition by Catherine Griffiths

by Catharina van Bohemen

exhibition review, Art New Zealand #196, Aotearoa NZ, November 2025

A paper record

by Catherine Griffiths introduction, Present Tense : Wāhine Toi Aotearoa — a paper record., Aotearoa NZ, May 2023

An installation on an installation on an installation ...

by Catherine Griffiths

artist statement, »catherine griffiths : SOLO IN [ ] SPACE« A documentation, Pocca, China

September 2021

A Paper Vehicle

by Catherine Griffiths and

Bruce Connew

Dwelling in the Margins, Gloria Books, 2020

Figures that don’t add up

by Catherine Griffiths

Eye Blog, UK, March 2019

1997–2017, 43 Black Pins, 40 men, 3 women

by Catherine Griffiths

The Spinoff, Aotearoa NZ, August 2018

Power in the Poster

by Catherine Griffiths

Designers Speak (Up), Aotearoa NZ, August 2018

Peace

by Catherine Griffiths

Word—Form, Australia, 2018

Porto Design Summer School 2017

by Catherine Griffiths

review, looking back on the fifth edition, Portugal, April 2018

Notes from ‘Designing the perfect photobook’

notes from a short talk as part of a panel discussion, PhotobookNZ, Aotearoa NZ, March 2016

A meditation

Sir Ian Athfield, 1940 — 2015

by Catherine Griffiths

Architectural Centre, Aotearoa NZ,

April 2015

The Design Kids interview

interview with The Design Kids, Australia, July 2015

A Playlist : CG >> CG

by Catherine Griffiths

DPAG Late Breakfast Show, Aotearoa NZ, August 2014

Body, Mind, Somehow: The Text Art of Catherine Griffiths

by Gregory O’Brien

Art New Zealand #150, Aotearoa NZ, 2014

Nothing in Mind

by Chloe Geoghegan

typ gr ph c, Aotearoa NZ, August 2014

typ gr ph c in Strips Club

by Catherine Griffiths

Strips Club journal, Aotearoa NZ, March 2014

In the Neighbourhood

by Catherine Griffiths

Desktop #294, Australia, 2013

Interview

by Heath Killen

interview for Desktop #294, Australia, 2013

FF ThreeSix

by Catherine Griffiths

Typographica, March 2013

A note on the D-card

by Catherine Griffiths

Aotearoa NZ, April 2013

She’s Got Legs

by Lee Suckling

Urbis, Aotearoa NZ, January 2013

Truly, No Idea

by Catherine Griffiths

for Flash Forward, Desktop, Australia, November 2012

Look for the purple lining

by Catherine Griffiths

Eye Blog, UK, March 2012

Q&A TBI

interview with The Big Idea, Aotearoa NZ, June 2011

Shots in the air

by Catherine Griffiths

Eye Blog, UK, January 2011

John & Eye

by Catherine Griffiths

ProDesign 110, Aotearoa NZ, January 2011

Quite a Blast

by Catherine Griffiths

ProDesign, Aotearoa NZ, January 2011

Inner-City Modality

by Mercedes Vicente

ProDesign, Aotearoa NZ, August 2010

Beautiful World of Typography

by Catherine Griffiths

excerpt from a talk, Govett-Brewster Gallery, Aotearoa NZ, June 2009

For the record

by Catherine Griffiths

Introduction to For the record, TypeSHED11 11–15/2009, Aotearoa NZ, February 2009

Locating Our Feet

by Catherine Griffiths

Threaded, Aotearoa NZ, October 2008

Notes

on Feijoa

by Catherine Griffiths

ProDesign, Aotearoa NZ, April 2007

Life in Italics

by Helen Walters

Print, New York,

USA, September-October 2006

Writing by

Types

by Justine Clark

Artichoke, Australia, April 2003

|